Latest Precedential Claim Construction Cases: When There Is Enough Intrinsic Evidence To Determine Claim Meaning Of A ‘Coined’ Term—And When More (Extrinsic Evidence) Is Needed

Two recent precedential decisions of the Federal Circuit provide guidance on the contours of claim construction; more specifically, when intrinsic evidence is sufficient to determine claim meaning and when something more—extrinsic evidence—is required.

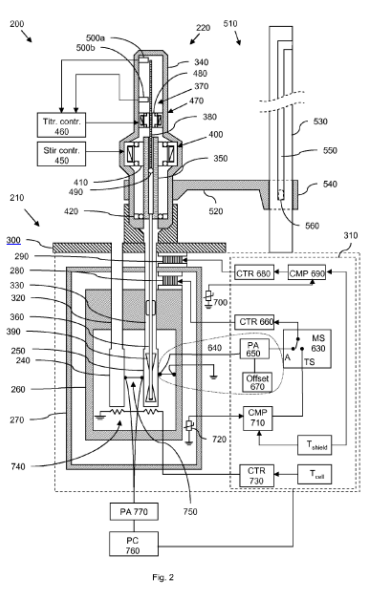

The first of these cases—Malvern Panalytical Inc. v. TA Instruments-Waters LLC, No. 2022-1439, 2023 WL 7171484 (Fed. Cir. Nov. 1, 2023)—involved two biomedical device patents, U.S. Patent Nos. 8,449,175 (the “’175 Patent”) and 8,827,549 (the “’549 Patent”). These inventions (depicted in Fig. 2 below) are multi-component devices consisting of, among other things, a titration needle that delivers titrant stored in the syringe to the sample cell where the observed biomolecular interactions take place. The machines measure the amount of energy absorbed or released during a chemical reaction.

Patent Owner Malvern Panalytical Inc. (“Malvern”) appealed a claim construction order construing the term “pipette guiding mechanism.”

At issue on appeal was whether the disputed term’s meaning covers only manual guiding mechanisms or covers both manual and automatic guiding mechanisms.

Malvern argued that neither the claim language nor the intrinsic record supported limiting the “pipette guiding mechanism” to manual operation. To counter, TA Instruments-Waters LLC and Waters Technologies Corporation (together, “Waters”), argued that “pipette guiding mechanism” is a coined term without plain and ordinary meaning to the skilled artisan. Waters narrowly argued that the coined term should be limited to manual operation given the statements in the specification and prosecution history.

The district court sided with the narrow ‘manual’ definition proffered by Waters.

The Federal Circuit reversed. Several reasons supported the reversal.

First, and looking to the claims, the phrase—“pipette guiding mechanism”—contained no limitations regarding manual movement of the mechanism. Malvern Panalytical, 2023 WL 7171484, at *4. Guided by the claim language, the Court simply stated: “Looking at the individual words . . ., the immediately apparent meaning is that a ‘pipette guiding mechanism’ is a mechanism that guides the pipette. The claim language contains no restrictions.” Id. at *12.

Second, the specification supported Malvern’s broad meaning of the disputed term. That is, there was no language describing the invention as limited to a manual guiding mechanism—“stating that ‘the present invention is, includes, or refers to’ a manual guiding mechanism, or ‘expressing the advantages, importance, or essentiality’ of a manual guiding mechanism.” Id. at *5. These italicized terms of art cabin the invention, and thereby narrow claim scope. That they were not present in Malvern’s patents was telling against the narrower construction.

Third, Waters’ argument based on the prosecution history was rejected. Waters argued that statements in the co-inventor declaration submitted during supplemental examination of the ’175 Patent narrowed the meaning of disputed term. Malvern Panalytical, 2023 WL 7171484, at *6. More specifically:

- During the supplemental examination, the examiner initially rejected claim 9 of the '175 patent as anticipated by the iTC200 manual.

- Malvern overcame this anticipation rejection by submitting co-inventor declarations establishing that the iTC200 was the original applicant's own prior art.

Id. at *8. Waters argued that these statements meant the '175 patent was coextensive with the iTC200, which is manually operated—thereby limiting the disputed term to such embodiments. Id. The argument, however, was rejected because “the co-inventor declarations d[id] not bear on the precise scope of the '175 patent; they establish only that the iTC200 embodied what was described and claimed in the '549 and '175 patents.” Id. at *14. In short, the Court confirmed that the focus of the analysis is on the “‘recited limitations of the claims, not features of a commercial embodiment of the invention.’” Id. (quoting Myco Indus., Inc. v. BlephEx, LLC, 955 F.3d 1, 15 (Fed. Cir. 2020))

The district court further held that plain and ordinary meaning could not apply since the coined term was not “known in the art or readily understandable to the skilled artisan. Malvern Panalytical, 2023 WL 7171484, at *6. The Federal Circuit rejected that view, finding that the district court erred because the plain and ordinary meaning of a claim term is tethered to “the context of the patent, which is the focus of [the] analysis”—not merely what is known in the art. Id. at *6.

In sum, because there was nothing in the intrinsic record, which cabined the meaning of “pipette guiding mechanism” to manual embodiments, the Federal Circuit held that the disputed term could extend to both manual and automatic embodiments of the mechanism.

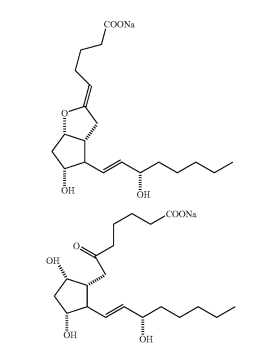

The second case—Actelion Pharms. LTD v. Mylan Pharms. Inc., No. 2022-1889, 2023 WL 7289417 (Fed. Cir. Nov. 6, 2023)—involved two pharmaceutical patents owned by Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd. (“Actelion”), U.S. Patent Nos. 8,318,802 (the “’802 patent”) and 8,598,227 (the “’227 patent”). The patents were directed towards epoprostenol formulations and improving stability upon their reconstitution with commercially available intravenous fluids. Such stability was unexpectedly found in the presence of an alkalinizing agent.

At issue on appeal was the meaning of the phrase: “a pH of 13 or higher.”

Actelion argued that “a pH of 13” in the context of the asserted claims was a value of acidity that is given as an order of magnitude that is subject to rounding. For example, Actelion's proposal would allow a pH of 12.5, which rounds to 13, to read on the claim limitation of “a pH of 13 or higher.” Actelion Pharms, 2023 WL 7289417, at *4.

Mylan argued that the proper construction cannot cover any pH values less than 13 and that the claim language did not provide approximation language (e.g. about a pH of 13 or higher) to support Actelion’s construction. Id. at *4 and *8.

In turning to the claims—and the lack of approximation language—the Court rejected Mylan’s argument reasoning that a bright line rule requiring approximation did not comport with the science underscoring the invention—i.e., “that the nature of measuring a pH value might . . . reasonably require a margin of error” and the creation of a “bright line” rule of construction for rounding would not be “plausible” in this context. Id.at *4. This reasoning also aligned with Actelion’s argument that “’it is not practically possible to measure exact pH values’” because to get an ‘exact’ measurement ‘one would have to count every hydrogen ion in solution, which is not scientifically possible.’” Id. at *4.

In turning to the specification, the Court confirmed the canon of construction that the “specification is always highly relevant to the claim construction analysis, and the single best guide to the meaning of a disputed term” Id. Notwithstanding this, the Court found that the “specification reveal[ed] that the inventor inconsistently described the level of specificity for a pH of 13.” Id. at *9. The specification, therefore, afforded no guidance.

In sum, the lack of clarity in the claims was only reinforced by an inconsistent specification while the prosecution history also compounded the ambiguity. Indeed, the Federal Circuit went as far as saying: “[T]he intrinsic evidence is rather equivocal. At the same time, the extrinsic evidence relied on by the parties—but unconsidered by the district court—appears highly relevant to how a person of ordinary skill would understand the language [viz.] ‘a pH of 13 [or higher].’” Id. at *3.

All of this led to the conclusion that the proper claim construction could not be reached without the “aid of extrinsic evidence—and that the district court should have considered, at minimum, the textbook excerpts offered and addressed by the parties.” Id. at *6. The Court further reiterated the teachings from Teva regarding extrinsic evidence:

The Supreme Court has made clear that there are cases where the district court must “look beyond the patent's intrinsic evidence and ... consult extrinsic evidence in order to understand, for example, the background science or the meaning of a term in the relevant at during the relevant time period.” . . . In such cases, the district court must “make subsidiary factual findings about that extrinsic evidence,” and such findings are the evidentiary underpinnings of claim construction.

Id. (quoting Teva Pharms. USA, Inc. v. Sandoz, Inc., 574 U.S. 318, 331 (2015)); see also id. at *6 (“It is not for this court to make those [factual] findings . . . Instead, we leave those and other relevant factual questions that might arise based on the extrinsic evidence, including the three textbooks, for the district court to address in the first instance.”).

Takeaways – Patent Prosecutors and Litigators

- The Malvern Panalytical decision involved a coined term. Contrary to Waters’ protestations, the Court held that even coined terms—such as, “pipette guiding mechanism”—could be afforded broad scope. Here, it meant both manual and automatic operations of the mechanism. This construction was held to be the plain and ordinary meaning of the term consistent with the intrinsic sources—in particular, the claim language and the specification.

- The lack of limiting language in the specification—for example, “the present invention is”—was relevant in Malvern Panalytical. The absence of this language ensured the claim term was not cabined by what was described in the specification. Had such limiting language existed in the specification, this would have narrowed the scope of the claim.

- When the meaning of a claim term cannot be determined from intrinsic sources (because of inconsistencies or otherwise), extrinsic evidence may be important for determining claim construction. This may come in the form of expert declarations, textbooks and scientific dictionary definitions at the time of the invention.

About Maynard Nexsen

Maynard Nexsen is a full-service law firm with more than 550 attorneys in 24 offices from coast to coast across the United States. Maynard Nexsen formed in 2023 when two successful, client-centered firms combined to form a powerful national team. Maynard Nexsen’s list of clients spans a wide range of industry sectors and includes both public and private companies.

Related Capabilities